On the morning of Aug. 5, 1964, rain clouds hung over Syracuse as hundreds of people gathered behind a chain-link fence at the edge of a runway at Hancock Airport. They held signs. They looked curiously at members of the Secret Service and the White House Press Corps, assembled nearby. They listened to transistor radios bringing news of unrest in the Gulf of Tonkin, off the coast of Vietnam. They peered skyward for some sign of the plane.

As if on cue, the clouds parted at 10 a.m. and, minutes later, the blue-and-white jet came into view. The crowd watched it land and taxi, saw the door swing open, caught a glimpse of a green silk dress and then, emerging into the light, came the president and first lady.

Lyndon Johnson and his wife, Lady Bird, had come to town to dedicate the newly-constructed Newhouse 1. It was the first of three planned buildings at Syracuse University that would be known as the S.I. Newhouse Communications Center in honor of the publishing magnate whose $15 million gift was the largest in the school’s history. Standing on the tarmac, Newhouse himself waited with his wife, Mitzi, to greet the Johnsons.

Samuel I. Newhouse had been born to poor immigrant parents on the Lower East Side of Manhattan, and now he stood next to the president of the United States. He understood, perhaps more than anyone else present, the significance of the scene. The evening before, at a dinner in his honor hosted by SU Chancellor William Tolley at the Hotel Syracuse, Newhouse had noted: “I cannot be unaware of a dramatic contrast that concerns my name. The first time it appeared anywhere was on a birth certificate written in a New York City tenement, where I was born. I’m proud of that. Tomorrow I will see my name inscribed on the wall of what is perhaps the most modern school of communication in the world. I am proud of that, too.”

A Moment in History

Lyndon Johnson was the first sitting president to visit Syracuse University since the 1930s, and Newhouse brought him there. The two men, who had met before, drove together in a car from the airport to campus, wending their way along a route crowded with an estimated 10,000 people hoping to see the president. Johnson was highly popular with an American public still reeling from the assassination of John F. Kennedy eight months earlier. He was also gearing up for an election the following November, and may have been heartened to see such an enthusiastic turnout in the majority Republican town.

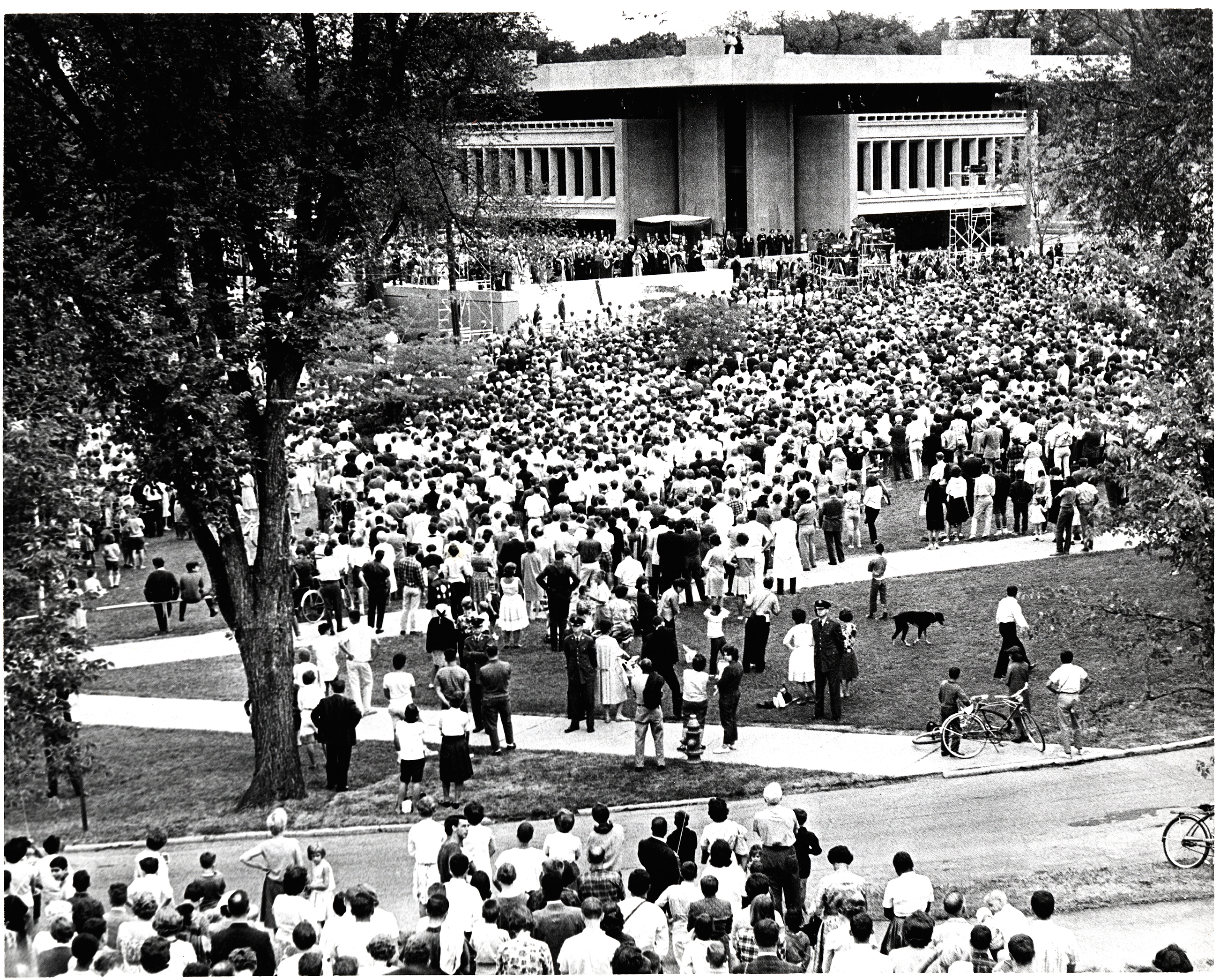

Another crowd waited for him on campus, covering the sloping hill from University Place back to the Hall of Languages and Maxwell Hall. The president and first lady stood on the plaza in front of the building flanked by the Newhouse family, Chancellor Tolley and New York Gov. Nelson Rockefeller and his wife, Happy. But Johnson looked grim as the ceremony commenced, and those who noticed his demeanor thought they knew what was on his mind: Vietnam.

The night before the Newhouse dedication, Johnson had gone on television to inform the nation of what he called “renewed hostile actions against United States ships on the high seas in the Gulf of Tonkin.” North Vietnamese vessels, he said, had twice attacked U.S. Navy ships, including the destroyer USS Maddox. The aggression, Johnson said, “brings home to all of us in the United States the importance of the struggle for peace and security in Southeast Asia.”

U.S. troops had been stationed in Vietnam since the Eisenhower administration, but always in an “advisory” capacity. Now, Johnson told the American people, it was time to take action. “I shall immediately request the Congress to pass a resolution making it clear that our government is united in its determination to take all necessary measures in support of freedom and in defense of peace in Southeast Asia,” he said.

The words were still fresh as Johnson readied to address the audience at Syracuse. Chancellor Tolley spoke first, introducing Newhouse. Quiet and averse to public speaking, Newhouse stood at the podium only a moment, to introduce the president. When LBJ, dressed in academic regalia, stepped up to the microphone, a rapt audience listened as he greeted the VIPs on the stage and noted, “On this occasion, it is fitting, I think, that we are meeting here to dedicate this new center to better understanding among all men. For that is my purpose in speaking to you.” With that, LBJ delivered the historic Gulf of Tonkin speech, again outlining the need for action in Vietnam. “The Gulf of Tonkin may be distant, but none can be detached about what has happened there,” he said. “Aggression—deliberate, willful and systematic aggression—has unmasked its face to the entire world. The world remembers—the world must never forget—that aggression unchallenged is aggression unleashed.”

Opening the Door

Johnson’s remarks were met with applause and, at the end, a standing ovation. Tolley presented him with an honorary doctor of laws degree, then LBJ then turned his attention to the four orange ribbons that had been strung across the opening of Newhouse 1. Newhouse’s wife was the first to clip a ribbon with a pair of gold scissors; his daughter-in-law, Susan, clipped the second. Lady Bird Johnson clipped the third and the president clipped the last, officially opening the Newhouse Communications Center at Syracuse University.

(View footage from the dedication ceremony)

Tolley presented both Johnson and Newhouse with golden keys, and Newhouse used his to unlock Newhouse 1. The 76,000-square-foot, flat-roofed building, designed in a cruciform shape, featured a spanning atrium lit by skylights in the 32-foot-high ceiling. On the wall was a bronze Jacques Lipchitz sculpture, “Birth of the Muses,” and a quote from Newhouse: “A free press must be fortified with greater knowledge of the world and skill in the arts of expression.”

Devoted at that time to print media, the building included classrooms, photography darkrooms and studios, design studios, faculty offices, a library and a public lounge. Enrollment that fall was 165 students.

The building had been six years in the making. After a chance meeting at the Waldorf-Astoria in New York City, Tolley and Newhouse had become friends, and around 1958 began discussing a proposed new building for the School of Journalism. At its founding in 1934, the school had been located in Yates Castle; but the building had been demolished in 1953 to make room for additions to the medical school, which had just changed hands from Syracuse University to the University of the State of New York. The School of Journalism needed a new, permanent home.

Newhouse’s initial gift of $1 million for the construction of a new building and $700,000 for operations was announced in 1960. But by 1962, the gift, along with the vision, had been expanded. That summer, the same summer he appeared on the cover of Time magazine, Newhouse pledged $15 million for what would become a three-building complex.

Newhouse chose up-and-coming architect I.M. Pei to design the first building. Pei, who would soon be tapped by Jacqueline Kennedy to design the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, was recognized for the Newhouse design in 1965 with the American Institute of Architects’ National Honor Award. The award citation noted that the building “exemplifies a powerful manipulation of mass and plane to enclose space. Its relation to its environment is superb, its materials simple and logical, its detailing excellent.”

That the building was located in Syracuse was not happenstance, and not solely the result of the relationship between Newhouse and Tolley. Newhouse’s connection to Syracuse stretched back to 1939, when he purchased two Central New York newspapers and merged them to create the Syracuse Herald-Journal. In 1942, he purchased the city’s other daily, the Syracuse Post-Standard. He also acquired Syracuse radio properties, and for a time made weekly train trips from New York City to Syracuse. Both of Newhouse’s sons, S.I. Jr. and Donald, attended Syracuse University. Newhouse received an honorary degree from the University in 1955 and was named to the Board of Trustees in 1959. “The City of Syracuse has a very special place in my heart,” he once said. And in a letter to Johnson a week after the dedication, Newhouse called Aug. 5, 1964, “my happiest of days.”

A Legacy Continues

In 1971, when the School of Journalism merged with the Department of Television and Radio, the school was re-named the S.I. Newhouse School of Public Communications and became the most comprehensive, stand-alone school of its type in the nation. Three years later, Newhouse saw the opening of the second building in the complex, Newhouse 2, which was dedicated with a keynote address by William S. Paley, chairman of the board of CBS.

Newhouse died in 1979, and control of his publishing empire—which by then included 31 newspapers, seven magazines, six television stations, five radio stations and 20 cable television systems—passed to his sons. Both men and their families were present in 2007 when the third building, Newhouse 3, was dedicated by Chief Justice of the United States John G. Roberts.

When Newhouse died, Dean Henry Schulte noted: “Mr. Newhouse maintained a keen, penetrating interest in the school, but never by word or gesture interfered in the management or growth of the school. It was if he said, ‘I’ll give you the tools. Seek excellence.’”

—Wendy S. Loughlin